1.1. Python scientific computing ecosystem¶

Authors: Fernando Perez, Emmanuelle Gouillart, Gaël Varoquaux, Valentin Haenel

1.1.1. Why Python?¶

1.1.1.1. The scientist’s needs¶

- Get data (simulation, experiment control),

- Manipulate and process data,

- Visualize results, quickly to understand, but also with high quality figures, for reports or publications.

1.1.1.2. Python’s strengths¶

- Batteries included Rich collection of already existing bricks of classic numerical methods, plotting or data processing tools. We don’t want to re-program the plotting of a curve, a Fourier transform or a fitting algorithm. Don’t reinvent the wheel!

- Easy to learn Most scientists are not payed as programmers, neither have they been trained so. They need to be able to draw a curve, smooth a signal, do a Fourier transform in a few minutes.

- Easy communication To keep code alive within a lab or a company it should be as readable as a book by collaborators, students, or maybe customers. Python syntax is simple, avoiding strange symbols or lengthy routine specifications that would divert the reader from mathematical or scientific understanding of the code.

- Efficient code Python numerical modules are computationally efficient. But needless to say that a very fast code becomes useless if too much time is spent writing it. Python aims for quick development times and quick execution times.

- Universal Python is a language used for many different problems. Learning Python avoids learning a new software for each new problem.

1.1.1.3. How does Python compare to other solutions?¶

Compiled languages: C, C++, Fortran…¶

| Pros: |

|

|---|---|

| Cons: |

|

Matlab scripting language¶

| Pros: |

|

|---|---|

| Cons: |

|

Julia¶

| Pros: |

|

|---|---|

| Cons: |

|

Other scripting languages: Scilab, Octave, R, IDL, etc.¶

| Pros: |

|

|---|---|

| Cons: |

|

Python¶

| Pros: |

|

|---|---|

| Cons: |

|

1.1.2. The Scientific Python ecosystem¶

Unlike Matlab, or R, Python does not come with a pre-bundled set of modules for scientific computing. Below are the basic building blocks that can be combined to obtain a scientific computing environment:

Python, a generic and modern computing language

- The language: flow control, data types (

string,int), data collections (lists, dictionaries), etc. - Modules of the standard library: string processing, file management, simple network protocols.

- A large number of specialized modules or applications written in Python: web framework, etc. … and scientific computing.

- Development tools (automatic testing, documentation generation)

See also

Core numeric libraries

Numpy: numerical computing with powerful numerical arrays objects, and routines to manipulate them. http://www.numpy.org/

See also

Scipy : high-level numerical routines. Optimization, regression, interpolation, etc http://www.scipy.org/

See also

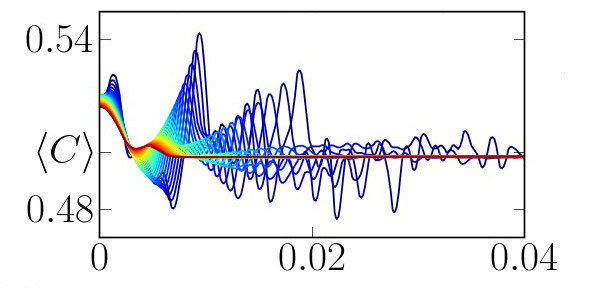

Matplotlib : 2-D visualization, “publication-ready” plots http://matplotlib.org/

See also

Advanced interactive environments:

- IPython, an advanced Python console http://ipython.org/

- Jupyter, notebooks in the browser http://jupyter.org/

Domain-specific packages,

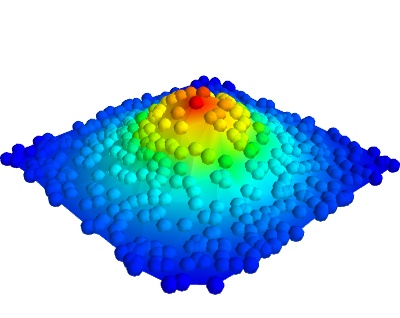

- Mayavi for 3-D visualization

- pandas, statsmodels, seaborn for statistics

- sympy for symbolic computing

- scikit-image for image processing

- scikit-learn for machine learning

and much more packages not documented in the scipy lectures.

1.1.3. Before starting: Installing a working environment¶

Python comes in many flavors, and there are many ways to install it. However, we recommend to install a scientific-computing distribution, that comes readily with optimized versions of scientific modules.

Warning

You should install Python 3

Python 2.7 is end of life, and will not be maintained past January 1, 2020.

Working with Python 2.7 is at your own risk. Do not expect much support.

Under Linux

If you have a recent distribution, most of the tools are probably packaged, and it is recommended to use your package manager.

Other systems

There are several fully-featured Scientific Python distributions:

1.1.4. The workflow: interactive environments and text editors¶

Interactive work to test and understand algorithms: In this section, we describe a workflow combining interactive work and consolidation.

Python is a general-purpose language. As such, there is not one blessed environment to work in, and not only one way of using it. Although this makes it harder for beginners to find their way, it makes it possible for Python to be used for programs, in web servers, or embedded devices.

1.1.4.1. Interactive work¶

We recommend an interactive work with the IPython console, or its offspring, the Jupyter notebook. They are handy to explore and understand algorithms.

Start ipython:

In [1]: print('Hello world')

Hello world

Getting help by using the ? operator after an object:

In [2]: print?

Type: builtin_function_or_method

Base Class: <type 'builtin_function_or_method'>

String Form: <built-in function print>

Namespace: Python builtin

Docstring:

print(value, ..., sep=' ', end='\n', file=sys.stdout)

Prints the values to a stream, or to sys.stdout by default.

Optional keyword arguments:

file: a file-like object (stream); defaults to the current sys.stdout.

sep: string inserted between values, default a space.

end: string appended after the last value, default a newline.

See also

- IPython user manual: https://ipython.readthedocs.io/en/stable/

- Jupyter Notebook QuickStart: http://jupyter.readthedocs.io/en/latest/content-quickstart.html

1.1.4.2. Elaboration of the work in an editor¶

As you move forward, it will be important to not only work interactively, but also to create and reuse Python files. For this, a powerful code editor will get you far. Here are several good easy-to-use editors:

- Spyder: integrates an IPython console, a debugger, a profiler…

- PyCharm: integrates an IPython console, notebooks, a debugger… (freely available, but commercial)

- Visual Studio Code: integrates a Python console, notebooks, a debugger, …

- Atom

Some of these are shipped by the various scientific Python distributions, and you can find them in the menus.

As an exercise, create a file my_file.py in a code editor, and add the following lines:

s = 'Hello world'

print(s)

Now, you can run it in IPython console or a notebook and explore the resulting variables:

In [1]: %run my_file.py

Hello world

In [2]: s

Out[2]: 'Hello world'

In [3]: %whos

Variable Type Data/Info

----------------------------

s str Hello world

From a script to functions

While it is tempting to work only with scripts, that is a file full of instructions following each other, do plan to progressively evolve the script to a set of functions:

- A script is not reusable, functions are.

- Thinking in terms of functions helps breaking the problem in small blocks.

1.1.4.3. IPython and Jupyter Tips and Tricks¶

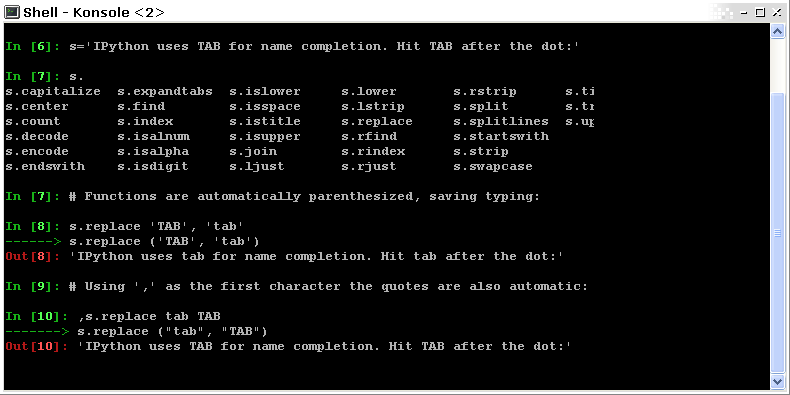

The user manuals contain a wealth of information. Here we give a quick introduction to four useful features: history, tab completion, magic functions, and aliases.

Command history Like a UNIX shell, the IPython console supports command history. Type up and down to navigate previously typed commands:

In [1]: x = 10

In [2]: <UP>

In [2]: x = 10

Tab completion Tab completion, is a convenient way to explore the structure of any object you’re dealing with. Simply type object_name.<TAB> to view the object’s attributes. Besides Python objects and keywords, tab completion also works on file and directory names.*

In [1]: x = 10

In [2]: x.<TAB>

x.bit_length x.denominator x.imag x.real

x.conjugate x.from_bytes x.numerator x.to_bytes

Magic functions

The console and the notebooks support so-called magic functions by prefixing a command with the

% character. For example, the run and whos functions from the

previous section are magic functions. Note that, the setting automagic,

which is enabled by default, allows you to omit the preceding % sign. Thus,

you can just type the magic function and it will work.

Other useful magic functions are:

%cdto change the current directory.In [1]: cd /tmp /tmp

%cpasteallows you to paste code, especially code from websites which has been prefixed with the standard Python prompt (e.g.>>>) or with an ipython prompt, (e.g.in [3]):In [2]: %cpaste Pasting code; enter '--' alone on the line to stop or use Ctrl-D. :>>> for i in range(3): :... print(i) :-- 0 1 2

%timeitallows you to time the execution of short snippets using thetimeitmodule from the standard library:In [3]: %timeit x = 10 10000000 loops, best of 3: 39 ns per loop

See also

%debugallows you to enter post-mortem debugging. That is to say, if the code you try to execute, raises an exception, using%debugwill enter the debugger at the point where the exception was thrown.In [4]: x === 10 File "<ipython-input-6-12fd421b5f28>", line 1 x === 10 ^ SyntaxError: invalid syntax In [5]: %debug > /.../IPython/core/compilerop.py (87)ast_parse() 86 and are passed to the built-in compile function.""" ---> 87 return compile(source, filename, symbol, self.flags | PyCF_ONLY_AST, 1) 88 ipdb>locals() {'source': u'x === 10\n', 'symbol': 'exec', 'self': <IPython.core.compilerop.CachingCompiler instance at 0x2ad8ef0>, 'filename': '<ipython-input-6-12fd421b5f28>'}

See also

Aliases

Furthermore IPython ships with various aliases which emulate common UNIX

command line tools such as ls to list files, cp to copy files and rm to

remove files (a full list of aliases is shown when typing alias).

Getting help

- The built-in cheat-sheet is accessible via the

%quickrefmagic function. - A list of all available magic functions is shown when typing

%magic.